Sustainable sector transformation. Why is it important, what is it and how can you achieve it? Based on a recently published report, we present a theory and practical guidelines to better understand complex systems, and to then develop strategies for contributing to systemic changes and sector transformation.

The journey to a world where agricultural-commodities are sustainably produced and traded is long. Despite decades of investments, many commodity sectors are still struggling with persistent problems such as poverty, pollution, land degradation, deforestation and violations of labor and human rights. This does not mean there have not been positive changes: there are numerous examples of farmers moving out of poverty, of farming systems improving in productivity and natural resource use efficiency, of supply chain collaborations which incentivize actors to invest in more sustainable practices. However, impacts often tend to remain limited in scale or do not persist over time.

The pursuit to build competitive, social and environmental sustainable and resilient agro-commodity sectors is something we are passionate about at Aidenvironment. As consultants, we engage with numerous organizations and support them in piloting new concepts and developing actionable insights. One of the lessons we have learned in the past decade is that large-scale and long-term change also requires strategies that address the root causes of structural weaknesses in the underlying systems. Examples of structural weaknesses include price volatility, natural resource depletion, poor organization of the production base, and the absence of services. In doing so, working in partnership is critical: private, public and civil society organizations all have a role to play. True sustainable transformation of commodity sectors requires a coordinated systems approach with a long-term vision and complementary strategies aimed at the root causes of persistent problems.

However, understanding such systems, let alone changing them is complex. Before you know it, you get tangled up in a web of actors, factors, and relationships without a sense of where to start and where to go. To overcome this challenge, we developed a theory and practical guidelines to understand and identify the key elements of complex systems, as well as the root causes of poor performance from a systems perspective. The framework has been developed with the perspective of a single commodity (e.g. coffee), applicable at different intervention levels (e.g. a country, a subnational jurisdiction or landscape) and for different types of commodities (e.g. vegetables, forestry, mining).

Key in the theory is to distinguish between two perspectives: the system perspective and the root causes perspective. The first relates to specific interconnected components that together form a system. We identify ten system components divided over three interconnected spaces:

- The landscape space represents the location (origins) of the production unit (which may be farms, , or mines) and its relationship with the surrounding communities and ecosystems.

- The market space refers to the relationships between producers, their organizations, service providers, value chains, and consumers within a sector.

- The governance space refers to the policy and regulatory environment, as well as the capability of the sector to collect revenue and reinvest it in a strategic manner. It also involves coordinating and aligning of stakeholders.

The model recognizes the dependency of the system upon the broader context of political, economic, environmental, sociocultural, and technological factors.

The ten system components of a sector and the five broader context factors

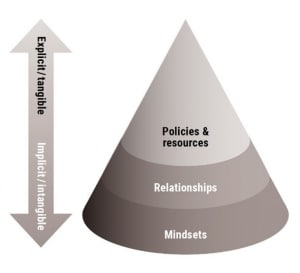

The second perspective looks at the explicit (or tangible) and implicit (or intangible) root causes of the structural weaknesses, or systemic issues, in and between the system components. They correspond to a great extent to what has identified as conditions for systems change.[1] They are:

- The explicit policies and resource levels of the actors. Policies refer to the policies, strategies, management systems (including processes and procedures) and incentive mechanisms which give direction to which practices are adopted by actors. Resources refer to human resources (knowledge, skills), financial resources, and other resources including the underlying business models, which influence the capability of actors to adopt practices.

- The (partly explicit) level of relationships and power relations between actors. This basically includes the relationships and networks between actors in a continuum between conflicts and cooperation. It also includes the way actors interact (their transparency and accountability).

- The (often implicit) underlying mindsets, mental models, norms, values, and belief systems. These aspects are considered the most fundamental elements in driving and sustaining transformational change, but are often neglected and, indeed, are the most difficult to change.

These root causes are generally intertwined with each other and interact, and this interaction may be mutually reinforcing or counteracting.

The three levels of root causes of underperformance that need to be addressed for transformative change are presented in the diagram below.

Sector transformation refers to the process of identifying and addressing all root causes of underperformance in the relevant system components. In addition to the above theory, we provides practical guidelines on how to start the journey of doing this. The guidelines follow three steps which includes the engagement of key stakeholders and building local ownership along the way:

- Sector diagnostics: This concerns creating a shared understanding of the system and its broader context by assessing the performance of the system components and the root causes of underperformance. The system components and root-cause models will serve as frameworks to structure the diagnostics.

- Vision and strategy development: This concerns formulating a vision shared by the key stakeholders of the desired future state of sector performance, and agreeing on an effective strategy to drive the transformation of the sector towards this vision. Effective strategies are vision-oriented, have an integrated nature (e. they address the linkages between system components and root causes), and are truly transformative in that they address the three levels of root causes for the identified systemic issues.

- Managing for transformation: This concerns coordinating the sector transformation process, with success factors such as quality of participation, convening and goal-setting, understanding the value of small wins in addressing complex systemic issues. Sector transformation also requires a continuous and iterative process of change backed up by sustained funding. Fundamentally, it also requires a process of monitoring sector transformation as a basis for learning, continuous improvement, and (most importantly) adaptive management. Monitoring sector transformation can be best done by adopting mixed methods, which combine qualitative and quantitative findings and the validation of key insights with relevant sector stakeholders without worrying about who contributed most to these changes.

This last point is important as the process of sector transformation should be iterative. Along the way, there will be changes in the dynamics of the sector and its broader context. Insights will emerge on which strategies are effective and which are not. New innovations can create new opportunities which were previously not considered possible. These changes require the continuous assessment of progress and context, and an openness to adapting the strategies, or even the vision itself.

We hope this document inspires and informs actors that, rather than creating ‘islands of success’, share the ambition to build competitive and sustainable sectors that have the resilience to remain so.

[1] FSG, 2018. The Water of Systems Change. By: Kania, J. Kramer, M., Senge, P